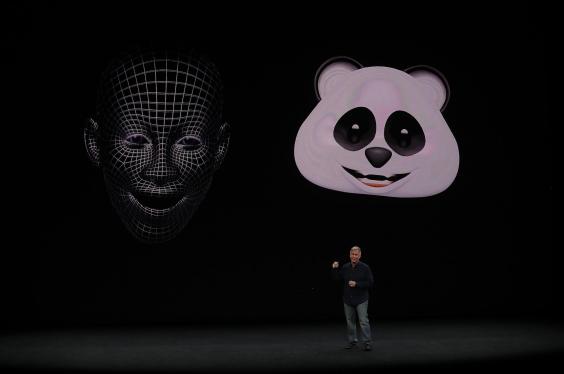

Poop that mimics your facial expressions was just the beginning.

It’s going to hit the fan when the face-mapping tech that powers the iPhone X’s cutesy “Animoji” starts being used for creepier purposes. And Apple just started sharing your face with lots of apps.

Beyond a photo, the iPhone X’s front sensors scan 30,000 points to make a 3D model of your face. That’s how the iPhone X unlocks and makes animations that might have once required a Hollywood studio.

Now that a phone can scan your mug, what else might apps want to do with it? They could track your expressions to judge if you’re depressed. They could guess your gender, race and even sexuality. They might combine your face with other data to observe you in stores – or walking down the street.

Apps aren’t doing most of these things, yet. But is Apple doing enough to stop it? After I pressed executives this week, Apple made at least one change – retroactively requiring an app tapping into face data to publish a privacy policy.

“We take privacy and security very seriously,” Apple spokesman Tom Neumayr said. “This commitment is reflected in the strong protections we have built around Face ID data – protecting it with the Secure Enclave in iPhone X – as well as many other technical safeguards we have built into iOS.”

Indeed, Apple – which makes most of its money from selling us hardware, not selling our data – may be our best defence against a coming explosion in facial recognition. But I also think Apple rushed into sharing face maps with app makers that may not share its commitment, and it isn’t being paranoid enough about the minefield it just entered.

“I think we should be quite worried,” says Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst at the American Civil Liberties Union. “The chances we are going to see mischief around facial data is pretty high – if not today, then soon, and if not on Apple then on Android.”

Apple’s face tech sets some good precedents – and some bad ones. It won praise for storing the face data it uses to unlock the iPhone X securely on the phone, instead of sending it to its servers over the internet.

Less noticed was how the iPhone lets other apps now tap into two eerie views from the so-called TrueDepth camera. There’s a wireframe representation of your face and a live readout of 52 unique micro-movements in your eyelids, mouth and other features. Apps can store that data on their own computers.

To see for yourself, use an iPhone X to download an app called MeasureKit. It exposes the face data Apple makes available. The app’s maker, Rinat Khanov, tells me he’s already planning to add a feature that lets you export a model of your face so you can 3D print a mini-me.

“Holy cow, why is this data available to any developer that just agrees to a bunch of contracts?” says Fatemeh Khatibloo, an analyst at Forrester Research.

Being careful is in Apple’s DNA – it has been slow in opening home and health data with outsiders. But it also views the face camera as a differentiator, helping position Apple as a leader in artificial intelligence and augmented reality.

Apple put some important limits on apps. It requires “that developers ask a user’s permission before accessing the camera, and that apps must explain how and where this data will be used,” Apple’s Neumayr said.

And Apple’s rules say developers can’t sell face data, use it to identify anonymous people or use it for advertising. They’re also required to have privacy policies.

“These are all very positive steps,” says Clare Garvey, an associate at Georgetown University’s Centre on Privacy & Technology.

Still, it wasn’t hard for me to find holes in Apple’s protections. The MeasureKit app’s maker tells me he wasn’t sensing much extra scrutiny from Apple for accessing face data.

“There were no additional terms or contracts. The app review process is quite regular as well – or at least it appears to be, on our end,” Khanov says. When I notice his app doesn’t have a privacy policy, Khanov says Apple doesn’t require it because he isn’t taking face data off the phone.

After I asked Apple about this, it called Khanov and told him to post a privacy policy.

“They said they noticed a mistake and this should be fixed immediately,” Khanov says. “I wish Apple were more specific in their App Review Guidelines.”

The bigger concern: “How realistic is it to expect Apple to adequately police this data?” Georgetown’s Garvey tells me. Apple might spot violations from big apps like Facebook, but what about gazillions of smaller ones? Apple hasn’t said how many apps it has kicked out of its store for privacy issues.

Then there’s a permission problem. Apps are supposed to make clear why they’re accessing your face and seek “conspicuous consent”, according to Apple’s policies. But when it comes time for you to tap OK, you get a pop-up that asks to “access the camera”. It doesn’t say, “Hey, I’m now going to map your every twitch.”

The iPhone’s settings don’t differentiate between the back camera and all those front face-mapping sensors. Once you give it permission, an active app keeps on having access to your face until you delete it or dig into advanced settings. There’s no option that says, “Just for the next five minutes.”

Overwhelming people with notifications and choices is a concern, but the face seems like a sufficiently new and sensitive data source that it warrants special permission. Unlike a laptop webcam, it’s hard to put a privacy sticker over the front of the iPhone X – without a fingerprint reader, it’s the main mechanism to unlock the thing.

Android phones have had face-unlock features for years, but most haven’t offered 3D face mapping like the iPhone. Like iOS, Android doesn’t make a distinction between front and back cameras. Google’s Play Store doesn’t prohibit apps from using the face camera for marketing or building databases, so long as they ask permission.

Facial detection can, of course, be used for good and for bad. Warby Parker, the online glasses purveyor, uses it to fit frames to faces, and a Snapchat demo uses it to virtually paint on your face. Companies have touted face tech as a solution to distracted driving, or a way to detect pain in children who have trouble expressing how they’re feeling.

It’s not clear how Apple’s TrueDepth data might change the kinds of conclusions software can draw about people. But from years of covering tech, I’ve learned this much: given the opportunity to be creepy, someone will take it.

Using artificial intelligence, face data “may tell an app developer an awful lot more than the human eye can see,” says Forrester’s Khatibloo. For example, she notes researchers recently used AI to more accurately determine people’s sexuality just from regular photographs. That study had limitations, but still, “the tech is going to leapfrog way faster than consumers and regulators are going to realise,” says Khatibloo.

Our faces are already valuable. Half of all American adults have their images stored in at least one database that police can search – typically with few restrictions.

Facebook and Google use AI to identify faces in pictures we upload to their photo services. (They’re being sued in Illinois, one of the few states with laws that protect biometric data.) Facebook has a patent for delivering content based on emotion, and in 2016, Apple bought a startup called Emotient that specialises in detecting emotions.

Using regular cameras, companies such as Kairos make software to identify gender, ethnicity and age as well as the sentiment of people. In the last 12 months, Kairos said it has read 250 million faces for clients looking to improve commercials and products.

Apple’s iPhone X launch was “the primal scream of this new industry, because it democratised the idea that facial recognition exists and works,” says Kairos chief executive Brian Brackeen. His company gets consent from volunteers whose faces it reads, or even pays them – but he says the field is wide open. “What rights do people have? Are they being somehow compensated for the valuable data they are sharing?” he says.

Comments

Post a Comment